TRUTH BE TOLD

IS AI MAKING LIFE DECISIONS FOR YOU?

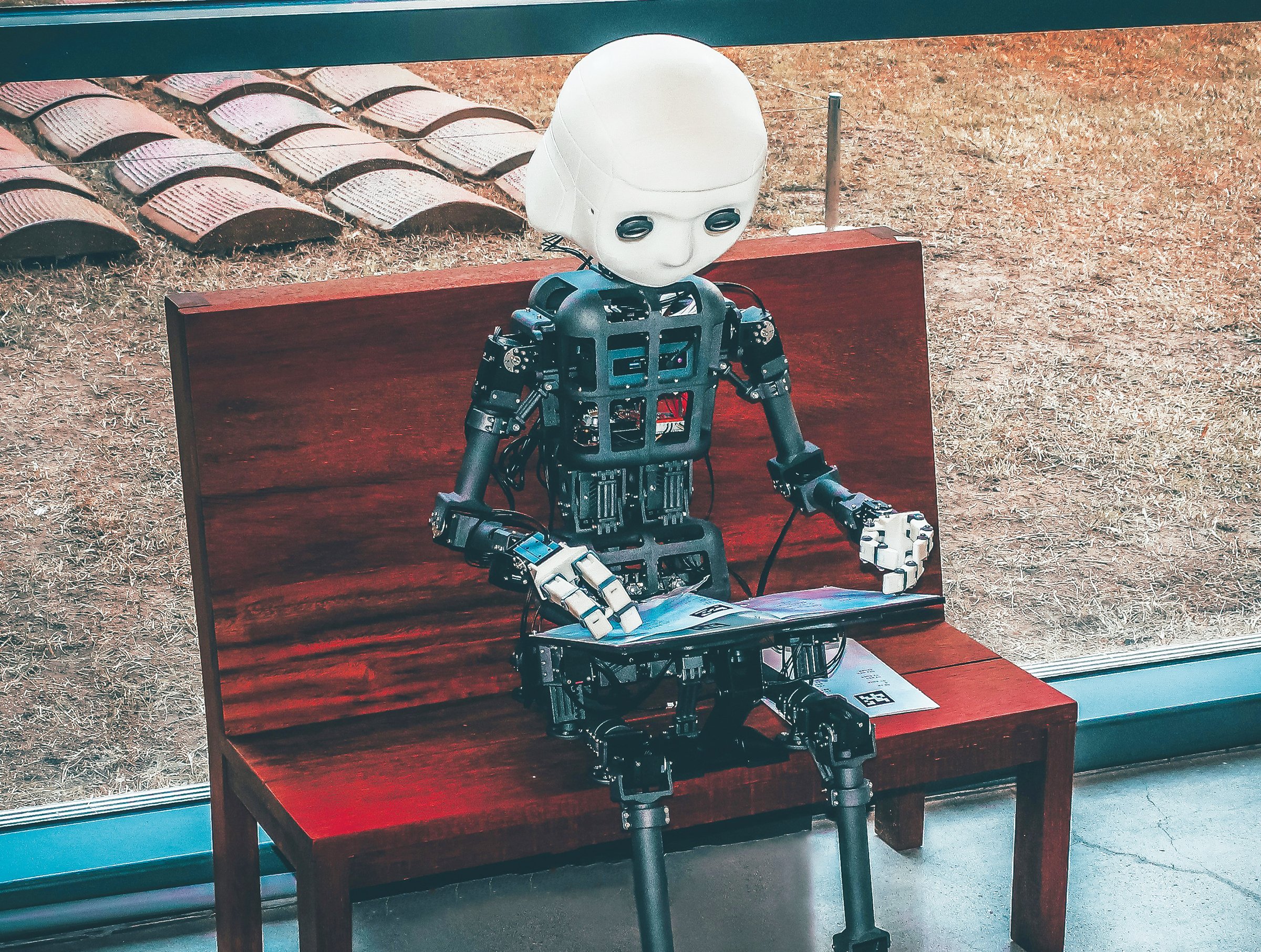

Our lives are virtually ruled by AI, but AI sometimes makes up stuff. Image credit: ANDREA DE SANTIS on Unsplash,

By DR VICKI BISMILLA

In an earlier article, I addressed the dilemma of Chat GPT reshaping the work of teachers and students and whether essays were the work of students or AI.

Now our lives are virtually ruled by AI. Search engines storing our searches, algorithms powering social media, our dependence on navigation apps and driverless cars and robots delivering food. Sometimes annoying AI interferences like autocorrect and copilot writing-assists interrupt our concentration. Organizations are using predictive analytics for outcomes to adjust goals and resources. In arenas of citizenship, spyware and crime investigations, facial recognition AI systems are informing investigative forces.

There are, of course, incredibly positive AI assists in medical diagnoses, imaging and robotics vastly improving healthcare. And AI is helping banks detect and prevent fraud by recognizing patterns, aberrations and suspicious activity.

But in the magazine Philosophy Now we start to see cracks in the AI nirvana. The editorial in their July 2025 issue states:

“To rely deliberately upon AI in science or philosophy, to work with it uncritically, is to choose to be away with the fairies. Not only does AI sometimes make stuff up (engineers euphemistically refer to it as ‘having hallucinations’), but its output often embodies the collective delusions of humanity, our prejudices and biases and preconceived assumptions and deep-rooted mistakes.”

These “hallucinations” are becoming increasingly problematic as reported in the MIT Technology Review (May 20, 2025) about a California judge who fined an elite legal firm $31,000 for filing court briefs (using AI) which were riddled with mistakes, false information and citing non-existing articles. The review cites three other cases in which California judges were frustrated with false court filings by lawyers using AI.

“Courts rely on documents that are accurate and backed up with citations – two traits that AI models, despite being adopted by lawyers eager to save time, often fail miserably to deliver.”

Even here in Ontario these false filings in courts are becoming a problem, says Maura Grossman who teaches at the School of Computer Science at the University of Waterloo. She says these are not isolated cases by inexperienced lawyers. “These are big-time lawyers making significant, embarrassing mistakes with AI.”

AI answers questions by quickly sweeping the internet, collecting whatever information is posted, often by unqualified, non-credentialed people, and disgorging it to the questioner. But the user needs to do some thinking, probing, fact-checking and analyzing and rather than just regurgitating, there needs to be reflective thought and informed opinion. And that is where the university/college dilemma becomes thorny. We are at post-secondary to think for ourselves, to search libraries (like we once did) and online but only so we can critique that information for ourselves using our own grey matter. As post-secondary students we need to be able to argue, disagree, form opinions and back-up our thinking with solid proof, using real, peer-reviewed articles in respected journals and publications.

The other problem with AI is that it is not human. As humans we have brains but we also have emotions, so when ChatGPT flings material at us can we analyze that material with compassion, empathy and ethics or do we just set aside these moral compasses like it was suggested by a billionaire recently who said the problem with the world today is empathy. Clearly as a tech billionaire, human emotions and ethics are bad for his business. And this disgorgement of randomly collected information also raises the question of what is the truth and what is fabricated and the issue of lying so convincingly that hordes of people believe. We have seen, repeatedly, that degenerates can be elected to lead nations based on their ability to lie convincingly and spread those lies using technology.

In his article Ethics for the Age of AI (Philosophy Now June-July 2025) Mahmoud Khatami poses this question:

“Imagine a self-driving car speeding down a narrow road when suddenly a child runs into its path. The car must decide: swerve and risk the passenger’s life, or stay the course and endanger the child?”

He continues, “This underscores the need for human oversight and careful ethical consideration, as machines lack compassion...”

Furthermore, algorithms reflect the biases of their human creators. So, an AI used in hiring will be programmed to sort out certain resumés based on the company’s historical hiring data. So, if the company has historically favoured male candidates it will prioritize male candidates over equally qualified women.

Khatami concludes:

“While AI can assist in making decisions, it cannot replace human judgment, empathy, or moral reasoning. It lacks the ability to understand context or feel compassion, underscoring the need for human oversight, transparency, and fairness. So the central question – Can machines make moral decisions? – remains unresolved.”

As Professor Max Gottschlich, (Austria) says to students in his article Studying Smarter with AI:

“In subjects involving large amounts of text, using AI seems to offer a convenient shortcut. But this is only a seductive semblance. Cutting through this illusion requires a quite developed insight into the point of studying at all.”

And that’s the point I’m making. We go to post-secondary to learn how to think, reflect critically, build on knowledge and extend it. Merely swallowing and regurgitating information is not learning, it’s becoming a patsy. In the days when students wrote lecture notes, sorted essential from extraneous, that in itself was an exercise in comprehension; and then pursuing pieces to understand more clearly through supporting data and in the case of science pursuing proof, that is learning.

For students there is the danger that AI can be a seductive illusion, arbitrarily feeding untested texts to closed minds sedated into believing “mission accomplished”.

Dr Vicki Bismilla is a retired Superintendent of Schools and retired college Vice-President, Academic, and Chief Learning Officer. She has authored two books.