A ROOM WITH A POINT OF VIEW

A TASTE OF FREEDOM

War not only changes the lives of victims and their societies, but also unexpectedly, changes the way they eat, forcing people to alter their recipes or even stop cooking altogether, threatening the survival of ancient cuisines. Image credit: MICHAEL BURROWS on Pexels.

By SHAGORIKA EASWAR

War changes every part of human culture: art, education, music, politics. Why should food be any different?”

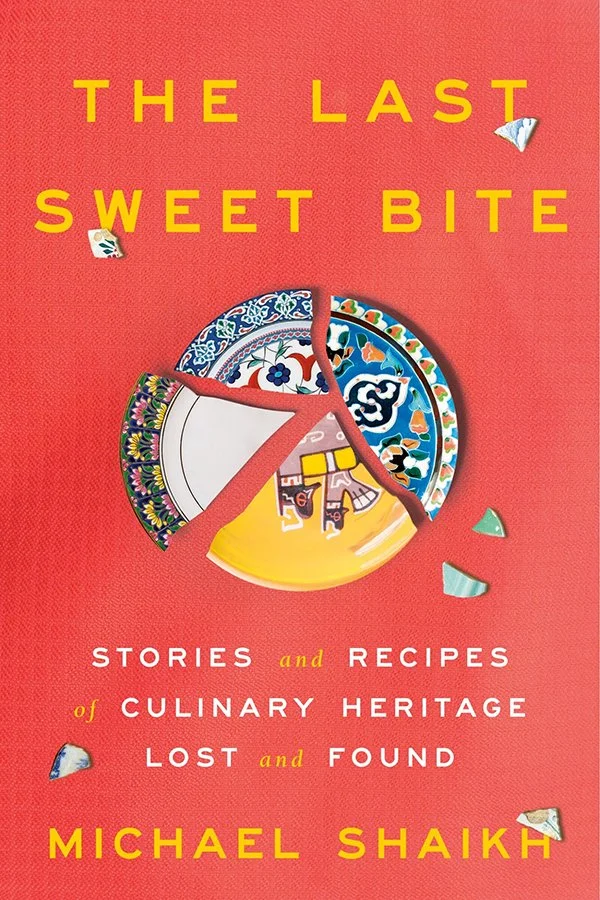

Writer and human rights investigator Michael Shaikh asks this question in his book, The Last Sweet Bite.

Early in his career, Shaikh noticed how war not only changed the lives of victims and their societies, but also unexpectedly, changed the way they ate, forcing people to alter their recipes or even stop cooking altogether, threatening the survival of ancient cuisines.

And yet, food culture hasn’t received the protections afforded to other forms of “culture”.

Shaikh proffers a startling – but one that makes me go, “but of course” – reason: sexism.

“This is mostly because a Global North elitist male perspective determines which aspects of culture should be elevated above others and are therefore worthy of protection. As a domestic chore done primarily by women, home-cooking is not valued in the same way as other aspects of heritage.”

He takes readers to different parts of the world where war and strife have taken their toll.

How during the war, Prague restaurants often had two menus – one for the occupier and one for the occupied. Old menus show how the Germans could order a variety of meat dishes while flour dumplings and thin watery sauces were offered to the Czechs.

In Afghanistan, Tamim tells him, “The wars have strangled Afghan culture. They have narrowed our language of food.”

Padmini, a woman in Jaffna, describes how home gardens were a source of culinary diversity.

Now, instead of making their own curry powders, many families are buying pre-made mixes.

“Not only are people forgetting our food and recipes from before the war, but also the flavours, how our food tasted before the war,” she laments.

I am reminded of Rajeev Surendra’s posts of his making traditional Tamil dishes from scratch – in his kitchen in Manhattan – in order to preserve that taste of home. There’s one of him in Toronto, excited to see red rice flour at Ambal Trading on Parliament Street.

He can’t find it in Manhattan, he says, and picks up a large bag to take back.

Describing the effect of the destruction of the fishing fleets in Gaza, Shaikh writes that when a community’s food culture is attacked, it can have cascading and devastating implications not only for its emotional and spiritual well-being, but also for its physical existence.

He meets Rohingya writers, photographers and poets forced to live in squalid refugee camps documenting their cuisine to keep their food culture from disappearing. Shaikh describes it as “the incredible food you may never know”.

Mihrigul, an Uyghur woman, sees young women from her community as yeast starters.

“Not for naan, of course,” she said with a quick giggle, “but for the future of Uyghur cuisine.”

Shaikh writes about how the coca leaf went from being valued like gold and offered to the gods by the Andean people to being thrust into the centre of the war on drugs.

And how amaranth, once a staple, nearly disappeared from Pueblo cuisine, substituted by “commodity foods”. It is sometimes referred to as the Fourth Sister to the sacred three sisters – corn, beans and squash – in many Native American nations.

Commodity foods are packaged shelf-stable foods (like white flour, sugar, processed peanut butter, dried pasta, processed cheese bricks, canned juices, meats, and vegetables, and powdered eggs and milk) provided to low-income Native communities by the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), writes Shaikh. He quotes Diné journalist Andi Murphy who says community foods are “seen as the latest incarnation of a violent and unequal historical relationship between tribes and the federal government”.

That said, Murphy also points out that while many see these foods only as colonial rations, it’s also true that canned foods are a necessity for people who live on reservations, often without running water or electricity.

It’s fascinating to see descriptions of alegrias, “round and crunchy confections of popped amaranth welded together with agave”. Rajgira chikki! Amaranth is known as rajgira in India, and there, like in many parts of the world, nutrient-rich ancient grains were replaced with ultraprocessed flours.

But, as someone tells Shaikh, things like amaranth don’t always disappear. Sometimes they are just waiting to be remembered.

The Last Sweet Bite by Michael Shaikh is published by Crown, $39.

In The Last Sweet Bite, a combination of memoir, travelogue and cookbook, Shaikh uncovers how humanity’s appetite for violence shapes what’s on our plates. And how much of what we eat today or buy in a market has been shaped by violence.

History and politics on the dinner table. With recipes from across the world.

Shaikh shares a Rohingya saying: Fet shaanti, duniyai shaanti – when your belly is peaceful, the world is peaceful.

And also several of the lost recipes people across the world are trying to save.