A ROOM WITH A POINT OF VIEW

ALL FLOURISHING IS MUTUAL

“Recognizing ‘enoughness’ is a radical act in an economy that is always urging us to consume more.” Image credit: SIKANDAR ALI on Unsplash.

By SHAGORIKA EASWAR

You know how if you are in the market for a new car and narrow it down to a preferred brand, all of a sudden, all you can see on the roads are cars of that particular brand?

Some years ago, my foodie brother sent me a recipe that required Panko breadcrumbs. I didn’t know what those were, I confessed, much to his shock and horror. He sent me a little blurb about them and an image of a packet. And guess what? After I hunted for them the first time, it was like I couldn’t walk into a grocery without seeing a display of Panko!

In yet another instance of this, I present the serviceberry.

Soon after I read The Serviceberry, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s luminescent book, my son mentioned Saskatoon berries (another name for serviceberries) that he tasted on a road trip across Canada. This particular road trip was years and years ago and he has never mentioned the berries earlier. And then just recently, I spotted a sign for picking your own Saskatoon berries in our neck of the woods. Never seen one before.

So just why am I getting all excited about the berries? It stems from my love for the book.

The slim volume packs so much beauty and wisdom that I start out marking passages to return to and then stop when it becomes evident I will be rereading the whole book after inhaling it in the first read.

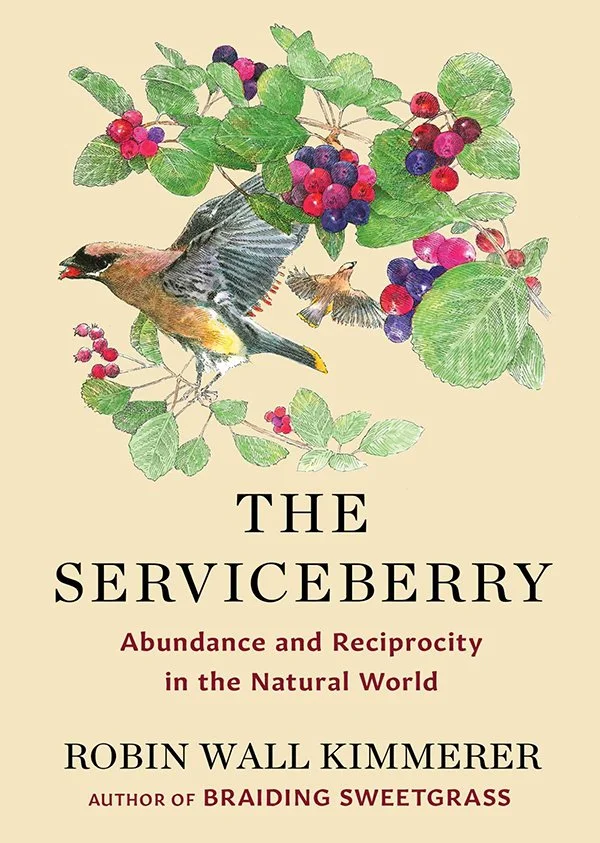

Illustrations by John Burgoyne introduce readers to her namesake, robin, “when we are both stuffing our mouths with berries and chortling with happiness”.

Can you picture a more delightful image?

I recognized that serviceberry is also called Saskatoon berry from her book as Wall Kimmerer shares its other names: Juneberry, Shadbush, Shadblow, Sugarplum, Sarvis...

“Ethnobotanists know the more names a plant has, the greater its cultural importance.” Which, if you think about it, should be obvious, but I for one had never thought of it quite like that.

She describes it as a calendar plant, important for “synchronizing the seasons of traditional Indigenous People, who move in an annual cycle through their homelands to where the foods are ready”.

The dried berries formed the base of the original energy bars.

A member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she is generous with her knowledge of their ways and their inheritance of a culture of gratitude and reciprocity.

“Recognizing ‘enoughness’ is a radical act in an economy that is always urging us to consume more.”

When everything is implicitly defined as scarce, she writes, the mindset that follows is based on commodification of goods and services.

She describes the work of ecological economists such as Dr Valerie Luzadis who define economics as “how we organize ourselves to sustain life and enhance its quality”.

Basically, the difference between the “cuddly capitalism” of the Nordic economies and the “cutthroat capitalism” of the US.

When she writes that local food economies are about being more than just freshness, food miles, etc., they are about a deep connection and honouring the gifts that are given to us, I am reminded of Grant’s Desi Achiever Joshna Maharaj. The food activist and chef brought about major changes in patients’ menus at hospitals. She worked closely with farmers who were excited to learn that what they grew would make patients feel better.

“Imagine a salad being served to a patient with a small note from the farmer who grew it,” she said. “I get goosebumps just thinking about how a patient would feel knowing that a farmer on a field somewhere was working to make him or her feel better.”

Wall Kimmerer shares the story of the hunter in the Brazilian rainforest who brought home a sizeable kill. A researcher thought he would smoke and dry some for use later, but the hunter invited neighbouring families and everyone enjoyed a feast.

Why didn’t he store the meat for himself, which is what the economic system of his home culture would predict, the researcher asked.

“I store my meat in the belly of my brother,” replied the hunter.

And thus we come to the sublime concept of gift economies in which gifts are not meant to be hoarded and made scarce for others.

Gatherings of our Potawatomi people often include a “giveaway” ... In the western world, someone celebrating a life event might expect to receive gifts, but in our way the equation is reversed. The ones who have been blessed with good fortune share that blessing by giving away.

Could that possibly be the origin of the return gifts at children’s birthday parties?

Among examples of gift economies Wall Kimmerer includes are ones you might expect – stands put up by neighbours to give away excess produce (zucchinis in particular!), repair cafés, freecycling events organized by students on university campuses.

The next on the list are obvious examples of a gift economy, and yet I am sure most of us haven’t viewed them in that light: Libraries with their infinite resources, the Little Free Library movement, and TikTok and YouTube videos that teach you everything from cooking and how to turn old leggings into a blouse.

This sharing of resources goes beyond the interpersonal .

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer is published by Scribner, $25.

The Dish with One Spoon Treaty extends it to the Indigenous People’s relationship with nature. It is based on the mutual understanding that Mother Nature has filled the shared lands with everything needed, it’s a gift. Ancient protocols guide the taking from the land.

The monster in Potawatomi culture is Windigo, she writes. He suffers from the illness of taking too much and sharing too little.

Her belief that all flourishing is mutual brings to mind the thinking that came to the fore at the height of the COVID pandemic. We were only as protected as our neighbours. Hoarding vaccines did us more harm – sharing it with nations with fewer resources kept not only people in those countries safe, by extension, it kept us safe, too.

This thinking resurfaces during a crisis. Floods, earthquakes. Or war. Huge donation drives are mobilized. And then we go to the grocery store and see people piling their shopping carts high with rolls of toilet paper. Signs limit the purchase to four per family. Who in their right minds would need or want more than four packs of 36 rolls each? And yet, obviously, some do.

Hence the limit.

“I’ve begun to think that berry-picking is the medicine we need to create a legion of land protectors,” writes the wise Wall Kimmerer.