A ROOM WITH A POINT OF VIEW

ROOTED IN FINDING CONNECTIONS THAT HEAL

In Cree and Ojibwa culture, trees are who and not what. Image credit: PRAMOD TIWARI on Unsplash.

By SHAGORIKA EASWAR

Award-winning author Tessa McWatt takes on personal and collective grief and the solace and inspiration to be found in connecting with nature – and each other – in Snag.

“The fires burning throughout Europe, North America and the Amazon, flash floods in England, climate refugees drowning off the coast of Greece: now I am inconsolable.”

The anxiety she experiences is contemporary and palpable, but also ancient and ancestral, she shares. It originates from her mother’s sorrow at losing a baby, but goes further back, and can be traced all the way to the enslaved Africans and indentured Indians and Chinese who worked her homeland’s sugar plantations and are her ancestors. That, as is evident in her mother’s case, “present-tense living with dementia does not erase trauma”.

No, in fact trauma lives just to the side of the present, accessible at any moment like opening a window.

Ancestral grief is low and sneaky, is dulled and yet can hit like a sniper. It’s grief shared with many people around the world for similar reasons of rupture from homelands. A grief that is not unlike solastalgia.

Solastalgia, as we know from many books on the subject, describes homesickness while at home.

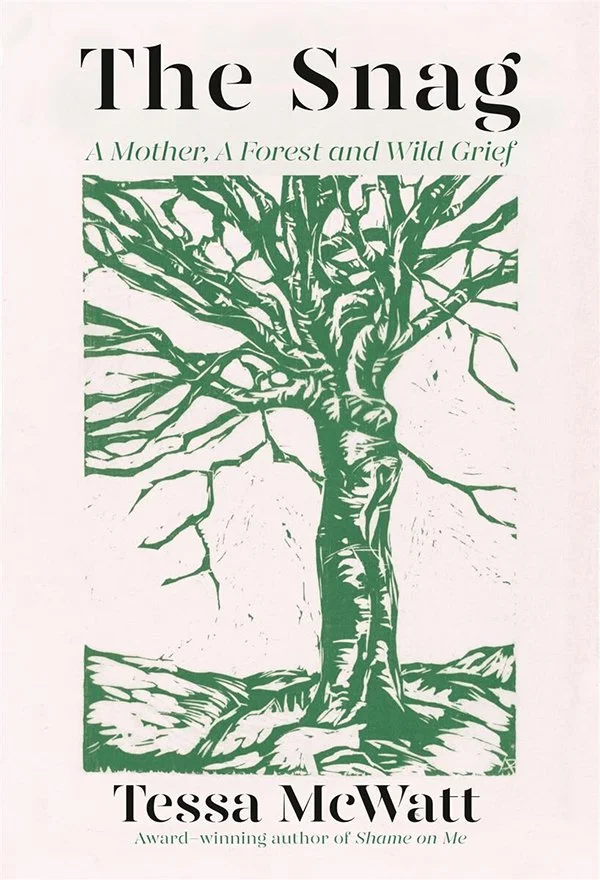

Snags, I learn from her book, are “the oldest trees, those that look nearly dead, the gnarled, pocked, twisted bodies of wood” – the mother trees that continue to tend to younger trees around them.

In Cree and Ojibwa culture, trees are who and not what. And that in Hinduism, trees are luminaries that have reached the highest plane of the plant world.

McWatt is no stranger to wild grief.

“It comes in waves, this sorrow that has me here at my desk riding one,” she writes, of a visit to Ontario in 2021. Based in the UK, she’s visiting her elderly mother at the height of COVID, at the height of learning stories of loss and death. Her closest friends are dealing with depression and cancer.

Death is growing its tree inside me. This tree will become a forest as I grow old, losing parents, siblings, friends, my own body.

Articles, scientific papers, blogs and books become her lifeline as she recognizes a need to hold onto facts as they slip from her mother. These facts and learnings she shares with her readers.

Her grief encompasses people in far-flung corners of the world.

And I learn more about places I thought I knew about. Bannerghatta National Park near Bangalore, for one. It is home, she writes, to Lambani, Iruliga and Hakki Pikki peoples, nomadic tribes who originated from Rajasthan, Sudan and Tamil Nadu. The Lambani celebrate Deepavali differently from how it is celebrated by most others in India. For the Lambani, is a time to pay tribute to the ancestors.

McWatt writes about the Gond community of Mendha village in Maharashtra, who set aside 12 per cent of their forests as sacred groves which house ancient trees and protect medicinal plants.

She feels guilty about taking long flights, sleeping in air-conditioning, eating well and the “towels and towels and towels all of us use for our many swims in the lake and that the hotel will have to launder”.

She worries when she reads that the World Bank has reported that India will be one of the first communities where the climate will shatter human survivability limits.

Readers might identify with her decision to eat vegan to mitigate her feelings of panic and her desire to be less of the problem than she feels she already is.

And yet, as she notes, the salad comes wrapped in plastic, the leaves have been washed in bleach... This salad’s crispness is the result of low wages, precarious living, pesticidal genocide and preservatives.

The Snag by Tessa McWatt is published by Random House Canada, $36.

Snag is about a multitude of griefs, large and small, in our families, friendships, communities and worldwide.

At the same time, it is also about finding collective solace in a multitude of places.

“Who owns this forest?” one of the elders of the Mendha community said. “Not the government, not the village, nor any of us. The real owners are those not yet born.”

There is endless grief, notes McWatt, but there is also endless reconstruction.